International Women’s Day 8th March 2021 International Women’s Day 8th March 2021

AETHELFLAED Myrcna hlæfdige (Lady of the Mercians) |

What we know of anyone in Anglo-Saxon times is drawn from a limited number of sources. The best known is the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle which is an amalgamation of various other sources, some copied from each other but with additional insertions. In the main the records are brief. Sometimes, historians are able to supplement these records with information found in surviving charters and other chronicles.

From these sources we can say that in the year 869 or 870, a noblewomen from Mercia named Ealhswith, wife of Alfred a ‘prince’ of Wessex, gave birth to a daughter called Aethelflaed. Five other children would follow over the years but Aethelflaed was the eldest. Then in 871, following the death of Alfred’s brother (and the previous deaths of his other brothers) Alfred, perhaps unexpectedly, became King of Wessex and the family’s life changed significantly.

Nothing much is known about Aethelflaed’s early life but it is thought that she and her sisters was educated alongside their brothers. Once the Viking threat had been temporarily reduced somewhat, and in order to strengthen the alliance between Wessex and Mercia, Alfred arranged a marriage between Aethleflaed and Aethelred, Lord of the Mercians, who had been his ally and vassal for some years. At that time, Wessex and Mercia shared a common border and common threats from the Welsh kingdoms to the west and Vikings to the east. The date of the marriage is not known but extrapolating from known joint Mercian and Wessex activities and various charters, historians usually place the date as being 885(ish) which would have made Aethelflaed around 15 or 16 at the time. Aethelred was at least ten years her senior.

Nothing much is known about Aethelflaed’s early life but it is thought that she and her sisters was educated alongside their brothers. Once the Viking threat had been temporarily reduced somewhat, and in order to strengthen the alliance between Wessex and Mercia, Alfred arranged a marriage between Aethleflaed and Aethelred, Lord of the Mercians, who had been his ally and vassal for some years. At that time, Wessex and Mercia shared a common border and common threats from the Welsh kingdoms to the west and Vikings to the east. The date of the marriage is not known but extrapolating from known joint Mercian and Wessex activities and various charters, historians usually place the date as being 885(ish) which would have made Aethelflaed around 15 or 16 at the time. Aethelred was at least ten years her senior.

Husband and wife gave generously to various Mercian churches, built a new Minster at Gloucester (small but highly embellished) and created/fortified the borough of Worcester. An abstract of the charter relating to the latter says that:

Ealdorman Aethelred and Aethelflaed ordered the borough of Worcester to be built for the protection of all the people and they now make it known in this charter that they will grant to God and St Peter (Church of), and to the lord of the church, half of all the rights that belong to their lordship whether in the market or the street, both within the fortification and without, except that the wagon-shilling and load-penny at Droitwich should go to the king as they have always done. Otherwise, the fine for fighting, or theft, or dishonest trading, and the contribution to the borough wall and all fines for offences which carry compensation, are to belong half to the lord of the church.

Charters referring directly to Aethelflaed are mostly from the second half of the 880s and after 900. For example, a Mercian charter of 887 granting estates to the See of Worcester contains witnesses that include Aethelflaed “conjux” – meaning spouse or consort. A charter of 901 reveals Aethlered and Aethelflaed donating land and a golden chalice to the church at Much Wenlock. The lack of charters that refer to Aethelflaed during the 890s may have been in part because she was busy raising and educating her only child (only surviving child anyway), a daughter called Aelfwyn, whose birth is thought to have been within a few years of her parents marriage – so around 888. The first surviving mention of Aelfwyn herself comes from a charter of 903 where she acts as a witness. She would probably have been in her teens in order to act in this capacity, which supports a birth date in the late 880s. Around the same year (903), Aethelflaed gained a ‘foster son’ when Aethelstan the son of her brother Edward, was sent by his father to be raised and educated at the Mercian court. Edward (the Elder) had suceeded Alfred as King of Wessex after the latter’s death in 899. By this time Aethelred’s health appears to have been failing, judging by comments in later Irish sources and his absence from charter activities, and his wife took on an increasingly active governance role. He died in 911 aged around 50 or a little over – a very good age for those years.

The principle highlights of Aethelflaed’s rule and influence were:

909 – a joint Mercian and Wessex force raided Viking territory and liberated the bones of the Northumbrian saint Oswald from Bardney Abbey in Lincolnshire and took them to Gloucester where they were installed in the new Minster, renamed as St Oswalds Priory in his honour.

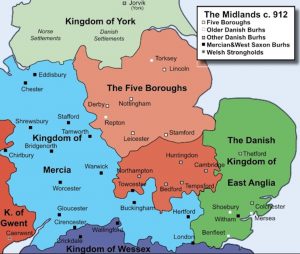

910 – another joint Mercian and Wessex force intercepted a Danish raiding army and defeated it at the Battle of Wednesfield. This opened the way for the recovery of the Danish Midlands and East Anglia over the next decade. The date of this battle is so close to that of the death of Aethelred that it is tempting assume the two are related but there is no surviving record to that effect.

911 – Aethelflaed was chosen by the Mercian nobility to be ‘myrcna hlaefdige’, Lady of the Mercians. Alfred had constructed a network of fortified boroughs in Wessex, and Edward and Æthelflæd now embarked on a programme of extending them to consolidate their defences and provide bases for attacks on Viking territories. Historian Sir Frank Stenton believed that Æthelflæd physically led Mercian armies on expeditions, which she herself planned. He commented: “It was through reliance on her guardianship of Mercia that her brother was enabled to begin the forward movement against the southern Danes, which is the outstanding feature of his reign”.

912 – Aethelflaed built defences at Bridgnorth to cover the crossing of the River Severn.

913 – She fortified Tamworth and Stafford to guard against Danish incursions.

Pre-914 – Hereford and Shrewsbury were fortified – the exact dates are unknown.

914 – A Mercian force repelled a Viking invasion from Brittany; Warwick was fortified.

915 – Chirbury was fortified to guard a route from Wales.

916 – Aethleflaed sent an expedition to Wales to avenge the muder of a Mercian Abbot. Her men destroyed the royal crannog of Brycheiniog and captured the queen and thirty-three of her companions.

917 – A Mercian army captured the key Danish town of Derby and its surrounding area, where it is recorded that Aethelflaed lost ‘four of her thegns who were dear to her’. Later that year, the East Anglian Danes submitted to Edward.

918 – Early in the year Aethelflaed took Leicester from the Danes without opposition, and a few months later the Danes of York offered to pledge their loyalty to her. This never happened however, as she died at Tamworth on June 12th of that year, aged about 48.

Her body was taken 75 miles to Gloucester where she was buried at St Oswald’s Priory. Aethlered was also buried there. The Mercian Register, states that Aethelflæd was buried in the east porticus. Archaeological excavation has found a building suitable for a royal mausoleum at the site of the east end of the church.

She was succeeded by her daughter Aelfwyn but only for a few months. Edward swept in, deposed her and took control of Mercia. Maybe he had less belief in his niece than he had in his sister. Or maybe he was not so much in awe of her. Loyalties could change swiftly in those times and it is ironic that when Edward himself died in 924 it was only days after supressing a rebellion by a combined force of Mercians and Welshmen in Chester.

Edward was succeeded by his son, and Aethelflaed’s foster son, Aethelstan. Aethelflaed’s influence lived on.

She had been the daughter of a king, the sister of a king, the foster-mother of a king, the niece of the last recognised king of Mercia on her mother’s side, the wife of a man who was king in all but name, and the undisputed leader of the Mercians at a critical time in history.